You are currently browsing the monthly archive for July 2012.

Americans With Disabilities Act

President Roosevelt in his wheelchair on the porch at Top Cottage in Hyde Park, NY with Ruthie Bie and Fala. February 1941.

To commemorate the 22nd anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the National Archives is featuring Presidential records related to disability history on a new web research page. Following that theme, below is a brief description of how FDR’s disability affected the design of his private retreat and of the first Presidential Library.

The FDR Library Building

The FDR Library was conceived and built under President Roosevelt’s direction during 1939-41 on 16 acres of land in Hyde Park, New York. Roosevelt decided that a dedicated facility was needed to house the vast quantity of historical papers, books, and memorabilia he had accumulated during a lifetime of public service and private collecting.

FDR considered himself to be an amateur architect, and was intimately involved in the design of the Library. He was particularly fond of the Hudson Valley Dutch Colonial style of architecture, and the Library was built in this fashion. The building provided not only museum space for visitors and a formal office for FDR but also storage areas for FDR’s vast collections.

Because a 1921 attack of polio had left Roosevelt paralyzed from the waist down, FDR primarily used personally-designed wheelchairs for daily mobility. Since he intended to personally and regularly use the vast collection of papers and manuscripts housed in the archives at the Library, he made sure the storage area aisles were built wide enough to accommodate his wheelchair. He also personally designed the document storage boxes initially used to house his papers. To enable his own lap-top style reading while in the storage areas, a special box type was created that could lie flat on the shelf, open in a clam-shell fashion, and act as a sort of paper tray. For preservation purposes, these boxes have since been replaced with newer, acid-free archival containers, but FDR’s original shelving remains in place in many parts of the Library storage areas.

An archivist at work in the FDR Library archival stacks, circa 1950s. The document boxes were designed by FDR.

Historic view of FDR Library archival stacks, featuring the original document boxes. FDR’s carefully arranged shelving remains in place in some areas of the Library today.

Top Cottage

Architectural design to accommodate FDR’s disability is also seen at Top Cottage, the Dutch Colonial style retreat FDR built for himself in 1938. FDR played a large role in the design of the building, which features a number of accommodations for FDR’s wheelchair. There are no steps to the first floor of the cottage, and a natural earthen ramp was built off the porch to provide access. Within the cottage, there are no thresholds on any of the doorways that might prohibit FDR from easily accessing any of the rooms, and all of the windows inside were built lower to the ground to give FDR clear views of the outside.

Find more information about about FDR and polio on our Library’s official website.

Carved Portraits of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt (MO 1941.4.12-13)

Noted African American artist Leslie Garland Bolling (1898-1955) presented these carved figures of the Roosevelts to the President and First Lady in 1940.

Born in Richmond, Virginia, Bolling was a largely self-taught artist who captured the attention of the art public with his busts and sculptures of working people and nude figures carved from wood. Bolling preferred to work with poplar because of its softness. He used a scroll saw to rough out the shape of a figure and a set of pocketknives to carve the details. He left each of his pieces unsanded, exposing his tool marks. Though these figures of the Roosevelts were painted, Bolling treated most of his works with only a light coating of wax.

Though Bolling never obtained enough funds from his art to work on his carvings full-time, he gained recognition for his art in the form of art shows and patrons. In 1935, he became the first African American to display his work in a one-man show at the Richmond Academy of Arts. He went on to exhibit his work in New Jersey, Texas, and New York. In 1938, with support from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Bolling and several local community leaders established the Craig House Art Center in Richmond. The Center offered training in art and art appreciation to African Americans and other minorities.

Bob Clark

Why should anyone care who works at the Roosevelt Library, you might ask? Well, it’s because we all view ourselves as just the most recent caretakers of the institution that FDR created and established. It was FDR’s dream that the Roosevelt Library would house the papers, records, and memorabilia of his life and presidency so that Americans of later generations could gain in judgment for the future. The Roosevelt Library itself is part of FDR’s legacy, and we all take our responsibilities very seriously. So I think it’s important for the people who pay our salaries—you the taxpayers—to know who we are and what we do here.

Why should anyone care who works at the Roosevelt Library, you might ask? Well, it’s because we all view ourselves as just the most recent caretakers of the institution that FDR created and established. It was FDR’s dream that the Roosevelt Library would house the papers, records, and memorabilia of his life and presidency so that Americans of later generations could gain in judgment for the future. The Roosevelt Library itself is part of FDR’s legacy, and we all take our responsibilities very seriously. So I think it’s important for the people who pay our salaries—you the taxpayers—to know who we are and what we do here.

I received my undergraduate and Master’s degrees in history at Texas Tech University. As a starving, penny-less student, I began working in Tech’s special collections library, the Southwest Collection. I’ll never forget sitting at the partner desk in the basement at the Southwest Collection going through my first box of completely unorganized archival materials that had been rescued from a woman’s attic in Lubbock. I fell in love with archival work.

But then I took an interesting turn. I went to law school and practiced law for seven years. While the law fascinated me, private practice did not. So with the turn of the millennium in January 2001, I asked myself “when were you happiest?” The answer: when I was an archivist. Soon, an archivist position opened up at the Roosevelt Library, and I moved to Hyde Park. It was one of the best decisions of my life. I was named Supervisory Archivist in February 2005.

Today, I oversee the care of the Roosevelt Library’s 17 million pages of manuscript materials, including the papers of FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt; printed materials, including FDR’s personal book collection of 22,000 volumes; and the audio-visual and photographic collections totaling some 150,000 items. I also manage our research operations, which hosts nearly 1,500 on-site researchers a year and responds to over 3,500 research requests that come in annually from all over the world. All this is done with one of the smallest (six people)—yet mightiest—archives staffs in the presidential libraries system.

The accomplishment of which I am most proud is that at the beginning of the renovation we managed to completely vacate the Library without ever closing our doors to research, even for one day. The experience proved that archival theories and practices work on any scale—whether organizing that box on the desk at the Southwest Collection in 1986, or moving all of the collections and research operations out of the Roosevelt Library in 2010.

I will always be grateful for the professional and personal satisfaction that the Roosevelt Library gives me. I work with some of the best and most conscientious public servants in government today. And every day, I get to come to work and be inspired by two of the greatest figures of the Twentieth Century, if not all time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Wagner Act Turns 77

When FDR signed the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) into law on July 5, 1935, he declared:

“A better relationship between labor and management is the high purpose of this Act. By assuring the employees the right of collective bargaining it fosters the development of the employment contract on a sound and equitable basis. By providing an orderly procedure for determining who is entitled to represent the employees, it aims to remove one of the chief causes of wasteful economic strife. By preventing practices which tend to destroy the independence of labor, it seeks, for every worker within its scope, that freedom of choice and action which is justly his.”

Because of the Wagner Act, union membership increased dramatically throughout the 1930s, and by 1940 there were nearly 9 million union members in the United States. The system of orderly industrial relations that the Wagner Act helped to create led to an era of unprecedented productivity, improved working conditions, and increased wages and benefits.

Today, the Wagner Act stands as a testament to the reform efforts of the New Deal and to the tenacity of Senator Robert Wagner in guiding the bill through Congress so that it could be signed into law by President Roosevelt.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, New York Governor Herbert Lehman, and Senator Robert F. Wagner at a campaign rally at Madison Square Garden, October 31, 1936. From the FDR Library Photo Collection, NPx 76-69(77).

For more on this topic, see the web article, FDR and the Wagner Act: “A Better Relationship Between Management and Labor.

During Phase 2 of the FDR Library’s building renovation special measures have been taken to protect the largest object in the Museum collection—FDR’s 1936 Ford Phaeton automobile. This vehicle, which features hand controls that allowed the President to drive it without the use of his legs, has been on display on the Library’s lower level for over 65 years. Because of its size, the car could not be removed from the lower level while demolition and construction work took place there. So conservators were brought in to build a special crate to protect the car and allow it to be moved to different locations on the lower level as renovation work progresses there.

The photographs below depict the extensive protective measures. The car was sealed inside a wood crate lined with Marvelseal, an aluminized nylon and polyethylene barrier film that resists the transmission of water vapor and off-gassing from wooden surfaces. The crate was lined with over 100 packs of desiccant to maintain proper humidity levels. A temperature and humidity sensor inside the crate constantly records readings. It can be viewed through the crate’s windows for easy monitoring. ShockWatch labels at several locations on the crate indicate any rough movement.

FDR’s car will be back on public display in the summer of 2013 when the Library’s building renovation is completed and the Museum premiers its new permanent exhibits.

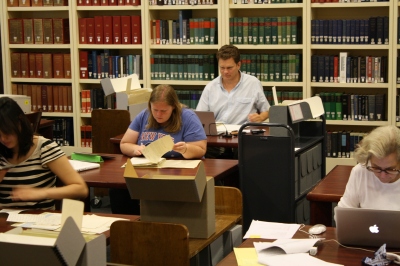

Last week 27 people traveled from all over the country, and even across the Atlantic Ocean, to visit the FDR Library’s research room. They came to interact with the estimated 17 million pages of primary source materials housed here within nearly 400 separate manuscript collections related to the Great Depression, the New Deal, and World War II.

FDR strongly believed that the records of government — those created by presidents, civil servants, and citizens alike — should be preserved, organized, and kept open for future generations. In developing this Library, he envisioned an institution both an archives and museum, to become a center for the study of the entire Roosevelt era.

In 1939 as plans for the Library were still being drawn, Roosevelt said of his voluminous papers:

I have destroyed practically nothing. As a result, we have a mine for which future historians will curse as well as praise me. It is a mine which will need to have the dross sifted from the gold.

He went on to say that neither he nor any scholar of his age could do that “sifting” task appropriately. Instead, we:

[…]must wait for that dim, distant period […] when the definitive history of this particular era will come to be written.

Today’s generations of researchers are some of the very people FDR sought to reach.

Research topics on Tuesday included education policy analysis; a study of the “Clergy Letters” detailing New Deal programs in rural communities; and Harry Hopkins’ wartime correspondence.

Vision for the Future of Democracy

71 years ago the Nation’s first Presidential Library opened its doors to researchers and museum visitors. In June of 1941 the threat of world war loomed heavily over the opening day proceedings. In his dedication address FDR said:

And this latest addition to the archives of America is dedicated at a moment when government of the people by themselves is being attacked everywhere. It is, therefore, proof—if any proof is needed—that our confidence in the future of democracy has not diminished in this Nation and will not diminish.

There are now 13 Presidential Libraries within the National Archives and Records Administration, including one for every U.S. President since FDR.

Above: Watch a newsreel reporting on the Library opening

For more information: